Whale shark ‘bling’ could unlock mysteries of giants of the deep by Mark Erdmann

First published in Conservation International’s blog Human Nature. (Re-posted with Permission.)

Snorkeler swims with a whale shark on a recent tagging expedition. The more we learn about whale shark movements and behavior, the better we can protect them

Snorkeler swims with a whale shark on a recent tagging expedition. The more we learn about whale shark movements and behavior, the better we can protect them

— and the tourism dollars they bring to countries from Indonesia to Belize to the Seychelles. (© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann)

The whale shark is a heavyweight in more ways than one.

Rhincodon typus is the world’s largest fish, reaching a whopping 18 meters (59 feet) in length and weighing up to 21 tons.

Its economic impact is just as massive. A recent study on whale shark tourism in a single atoll in the Maldives showed that tourists there spend nearly US$ 10 million annually for the privilege of swimming with whale sharks. Countries as diverse as Belize, the Seychelles and Australia similarly nurture multimillion-dollar whale-shark tourism industries — often based on only short 6- to 12-week seasons when the whale sharks are present.

Despite their impressive size and economic stature, we surprisingly still know very little about whale sharks. Conventional wisdom suggests they are a highly migratory species that gathers seasonally in places including Ningaloo (Western Australia), Gladden Spit (Belize) or Isla Mujeres (Mexico) to gorge on planktonic feasts composed of krill blooms or the fertilized eggs from mass spawning of corals or reef fishes.

Most of these aggregations comprise predominantly young males; we know very little about where they go when the feast is over, and we know even less about where the females and large adult males spend their time. Unlike whales and dolphins, which must frequently surface to breathe air, whale sharks can literally disappear for months or years into the depths — keeping the secrets of their daily lives hidden from humans.

That may be about to change.

Where do they go?

In past blogs, we’ve reported on our scientific efforts to better understand whale shark populations in Cenderawasih and Triton bays in the Bird’s Head Seascape. The whale sharks in the Bird’s Head are seemingly unique in that they can be found year-round within the region, and their preferred food seems to be schools of silverside baitfish known locally as “ikan puri.” In the past six years they have driven a burgeoning tourism industry in these remote regions of West Papua, leading the Indonesian government to declare the whale shark a fully protected species in 2013 due to their economic value for tourism. Similar economic arguments also convinced the government to protect both species of manta ray in 2014; no small feat considering that Indonesia for the past 30 years has been the world’s largest fishery for sharks and rays!

Since 2009, whale shark tourism to Cenderawasih Bay has been growing rapidly. (© Conservation International/photo & video by Mark Erdmann)

But in order to better protect the whale sharks in the Bird’s Head, it is important to understand their movement patterns and behavior. For instance, we need to know if these sharks truly reside year-round in the region, or if they wander outside Indonesian waters and into areas where they may be at risk of being snared in massive drift gill nets or deep-water trawl fisheries.

To find out, we’ve been working with the Indonesian Ministry of Fisheries and local agencies to deploy satellite tags on these massive animals in hopes of divulging their secrets. While these tags have provided data suggesting the animals stay close to home, we’ve struggled with the fact that the tags (affixed with a small titanium dart and monofilament tether below the shark’s dorsal fin) frequently detach from the sharks within a few weeks of deployment, giving us only a tantalizingly brief snapshot of their behavior.

Enter a new kind of shark-tracking technology.

How to tag a whale shark

To surmount the problem of sharks’ shedding their satellite tags, many scientists in the past decade have turned to “fin-mounted” satellite tags, which are literally bolted into the animal’s fin and can transmit data for a year or more. This technique is now commonly used for animals ranging from reef sharks and great whites, but it has not been widely used on whale sharks, which are simply not possible to hook on a line (due both to their immense size and lack of interest in eating bait on a hook!) and restrain at the side of a boat while a tag is affixed to their fin.

Just two weeks ago, however, a team from CI Indonesia (including Abraham Sianipar, Ronald Mambrasar, Schannel van Dijken and myself), the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, the State University of Papua and the Cenderawasih National Park Authority took advantage of an increasingly common occurrence: whale sharks in Cenderawasih are often accidentally caught in bagan fishing nets in the pre-dawn hours as they feed on the baitfish that the nets are targeting.

Bagan “lift-net” fishing boat in Cenderawasih Bay; bagans target the “ikan puri” baitfish which the whale sharks of Cenderawasih count as their favorite food!

Bagan “lift-net” fishing boat in Cenderawasih Bay; bagans target the “ikan puri” baitfish which the whale sharks of Cenderawasih count as their favorite food!

Below: Whale shark caught in bagan net in Cenderawasih Bay. (© Conservation International/photos by Mark Erdmann)

Working with the bagan fishermen, we were able to get into the nets with the whale sharks (which thankfully are surprisingly docile after they realize they have been caught!) and perform a quick operation with an underwater pneumatic drill to mount specialized satellite tags to the dorsal fins of five whale sharks, which ranged from 4.5 to 7 meters long (14 to 23 feet).

CI’s Schannel van Dijken swims with a recently tagged whale shark. The tag is visible on the shark’s dorsal fin. (© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann).

CI’s Schannel van Dijken swims with a recently tagged whale shark. The tag is visible on the shark’s dorsal fin. (© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann).

Don’t mean a thing without the ‘ping’

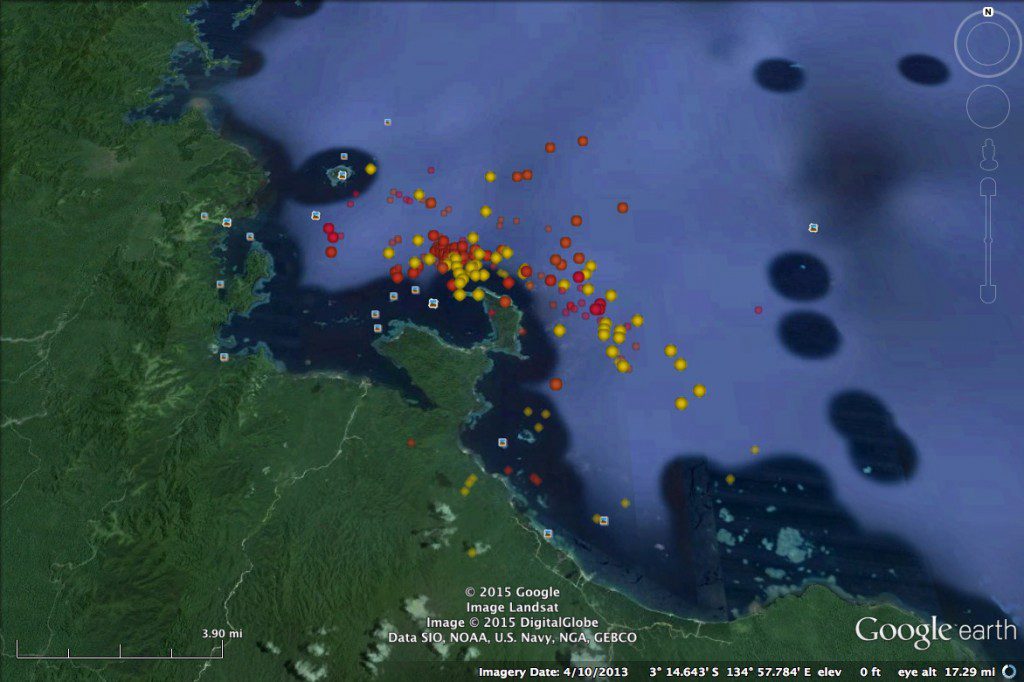

Much to our delight, the sharks’ “bling” have started to “ping” — transmitting location and diving behavior data beautifully on a nearly daily basis since tagging. Though only a few weeks have passed, we can now see that they are indeed mostly cruising around southern Cenderawasih Bay, with no indication of moving from their rich food source (why go on a long journey if you have everything you need at home?) They occasionally dive to 80–100 meters (260-330 feet) deep, but they spend upwards of half their time in shallow water less than 20 meters (66 feet) deep — a good thing for divers and snorkellers!

Whale shark movements in souther Cendrawasih Bay, Indonesia – showing the sharks remaining very close to Kwatisore Bay. This data was captured in the first two weeks after the fin-mounted satellite tags were affixed to the sharks. (© Conservation International).

Whale shark movements in souther Cendrawasih Bay, Indonesia – showing the sharks remaining very close to Kwatisore Bay. This data was captured in the first two weeks after the fin-mounted satellite tags were affixed to the sharks. (© Conservation International).

The tags were custom-designed for us by our partner Wildlife Computers to have a long battery life, which we hope will ensure these tags continue transmitting for up to two years.

Over that time, we expect to learn a lot more about the behavior and daily lives of these magnificent animals, which will help the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries and local management authories (including the Cenderawasih Bay National Park Authority and the Kaimana regency government) to better manage their populations and ensure they are providing sustainable benefits to local communities in the Bird’s Head through a healthy and responsible marine tourism industry.

Snorkelling with whale sharks in Cenderawasih Bay. (© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann)

Snorkelling with whale sharks in Cenderawasih Bay. (© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann)

Mark Erdmann is CI’s Vice President for Asia Pacific Marine Programs, now based in Auckland after 23 years in Indonesia. Mark would like to specifically acknowledge the generous support of guests of the True North expedition vessel, Matt Brooks and Pam Rorke Levy and Oceanmax/Propspeed for sponsoring the whale shark satellite tagging expedition in Cenderawasih.