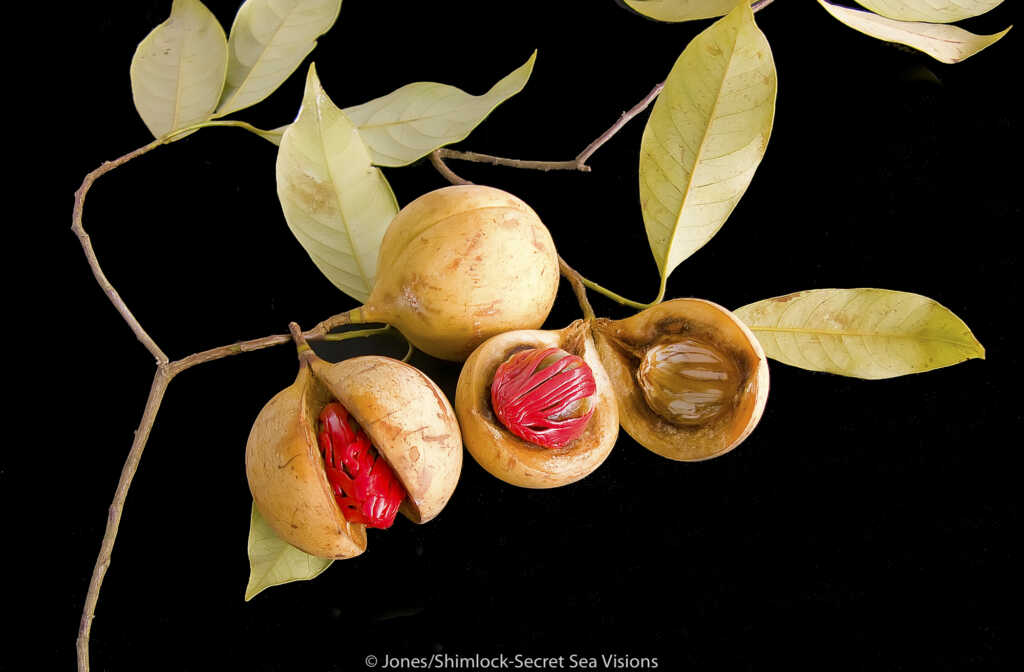

Papuan Nutmeg! It’s not the same species we know from the Banda Islands.

Administrator’s notes:

Did you know that there are several species of Nutmeg? (I didn’t!) According to British anthropologist Roy Ellen, the “original” nutmeg species, known from the days of the spice trade, was not the now-familiar Bandanese variety (Myristica fragrans) but the lesser known “long nutmeg” from Papua (Myristica argentea). Papuan nutmeg, known locally as “pala tomandin”, comes from the Fakfak/Kaimana forests of West Papua, near the popular dive destination of Triton Bay. (Incidentally, there is a third species native to SW India M. malabarica.)

The Bandanese species is often referred to as “true” or fragrant” nutmeg. It is most popular variety, with global distribution.

The two species look similar but, as its common name implies, the Papuan species, “long nutmeg” is more elongated and comes with its own chemical components giving it a unique flavor and fragrance.

The Bandanese species is round and is sometimes called the Common, True or Fragrant Nutmeg.

Both species are cultivated for the two spices that come from it’s yellow fruit: Nutmeg (the seed) and Mace (the red web-like seed covering, or aril). The yellow pericarp (fruit covering) is used to make jam, or is finely sliced, cooked with sugar, and crystallized to make a fragrant candy.

The following article about Papuan nutmeg is reprinted from the Inobu website,

A Sustainable Pathway for Papuan Nutmeg by Silvia Irawan

Family business: A local farmer and his family peel nutmeg in Air Besar hamlet in the West Papuan regency of Fakfak on Nov. 14. Farmers sell nutmeg beans at Rp 50,000 (US$3.50) per kilogram and flowers Rp 205,000 per kg.(Antara/Gusti Tanati)

Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) chairman Bahlil Lahadalia announced on Nov. 23 a plan by a Dutch company to develop 40,000 hectares of plantation in the West Papuan regencies of Fakfak and Kaimana. A month later, The Jakarta Post quoted a BKPM statement as saying that “the firm is committed to working with local nutmeg farmers in West Papua and providing technology for the nutmeg stripping, drying and cleaning process” and that “the cooperation will potentially employ 50,000 Indonesian nutmeg farmers”.

The details of the investment have yet to be made public and questions linger as to how the project will affect indigenous peoples and their forests.

In fact, 86 percent of land in Fakfak is covered by natural forests. The Mbham Mbhatta people, the customary owners of the forests, harvest the nutmeg that grows naturally in the forests just as they do other non-timber forest products. The nutmeg forest gardens form part of a rich and diverse forest mosaic covering the regency.

Responsible investment in West Papua is most welcome, but it is worth discussing the potential risks to the people and natural environment from the expansion of plantations.

For thousands of years, the spice trade has connected the archipelago of what is now Indonesia to the rest of the world. One of its main spices is nutmeg. According to British anthropologist Roy Ellen, the original nutmeg traded was not Bandanese nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), but long nutmeg (Myristica argentea Warb) from Papua. Papuan nutmeg, also known as pala tomandin, grows in the forests of Fakfak and Kaimana in West Papua.

Bandanese nutmeg is better known than Papuan nutmeg, particularly in Europe. In Indonesia, for instance, the government currently bases its national standard for nutmeg on the characteristics and properties of Bandanese nutmeg. So, all nutmeg exported is assumed to be Bandanese nutmeg as they share the same HS Code, a code used by customs authorities around the world for applying duties and taxes on internationally traded products.

Often perceived as inferior to Bandanese nutmeg, Papuan nutmeg has different chemical components, creating a unique flavor and fragrance. However, its potential is still largely untapped. Only recently has the government begun revising the national standard for nutmeg to accommodate Papuan nutmeg.

Farmers in Fakfak harvest nutmeg twice a year and sell it to informal traders who then supply it to regional traders. The price is set by a small number of regional traders who form an oligopoly. Farmers prefer to sell nutmeg raw for quick cash. They also spend a lot of money for the harvest as it is an important ceremony for the Mbham Mbhatta. Locals use nutmeg as currency and collateral for daily necessities or other expenses.

Adding a sole foreign investor on top of the current noncompetitive local nutmeg market without terms and conditions protecting indigenous nutmeg farmers can increase the vulnerability of farmers. An abrupt intervention and transformation in the nutmeg market will leave indigenous farmers, who produce and process nutmeg traditionally, behind.

At some point, given the inefficiencies of traditional production, indigenous farmers may be excluded from the nutmeg supply chain.

As the region’s nutmeg is not cultivated, the yield is currently relatively low and the quantity and quality of the Papuan nutmeg supply is not consistent. Changing harvest and post-harvest practices of farmers to improve the quality and quantity of nutmeg should be done through farmers’ groups.

However, the majority of Papuan nutmeg farmers do not belong to any farmers’ groups, and support is needed to increase participation in – and the management of – farmers’ groups.

Currently, there is no comprehensive data on traditional farmers. Yayasan Inobu, together with AKAPe, a local NGO based in Fakfak, has mapped 1,268 hectares of nutmeg forest gardens belonging to 659 farmers. This only covers 36 of the 142 villages in Fakfak. Without proper data, we can only guess the total potential yield and productivity of Papuan nutmeg in the regencies of Fakfak and Kaimana.

An industrialized agricultural commodity always brings risks to a society and its natural environment as it competes with other land uses, including forest conservation. There are four important risks that should be considered by potential investors.

First, any investment in the nutmeg industry in Papua should improve the production of the native variety of Papuan nutmeg (Myristica argentea Warb), rather than introducing Bandanese nutmeg (Myristica fragrans). Efforts to improve the production should preserve the ecological function of forests, and no forests should be cleared for new planting of nutmeg.

Second, the rights of indigenous farmers to the land should be acknowledged. Contractual arrangements for the production and sale of nutmeg to commercial entities should not diminish these ownership rights.

Third, the prospective investor should avoid establishing a plantation but should rather purchase nutmeg from indigenous farmers. Contracts should be made directly with producer organizations, such as indigenous farmer groups, based on fair prices and terms.

Fourth, investments should be made in downstream industries located in the regencies, which could include packaging and branding of raw spices, processing of fruits and facilities for extracting essential and fixed oils and oleoresins. Further processing of these extracts into consumer goods and cosmetics will provide greater employment opportunities for local people.

Silvia Irawan is executive director of Yayasan Inobu, an Indonesian nonprofit research institute, who has a PhD in Environmental Management and Development from the Australian National University.

This article has been published on The Jakarta Post and can be seen at the following link:

https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2020/12/29/a-sustainable-pathway-for-papuan-nutmeg.html