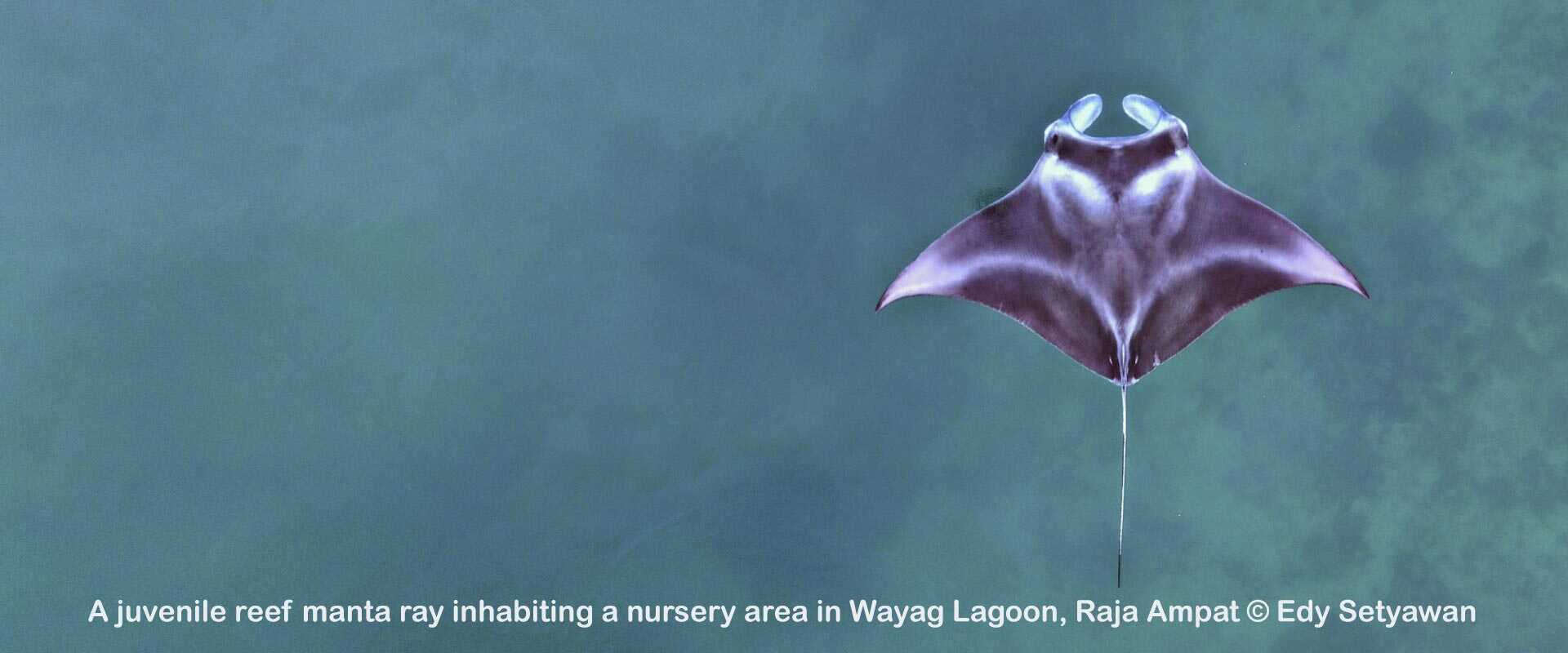

Indonesian Scientists Uncover World’s First Confirmed Manta Ray Nursery in Raja Ampat’s Wayag Lagoon by *Edy Setyawan

Did you know that newborn reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) – some of which can be found in Raja Ampat, West Papua – must live independently without parental care? Have you ever imagined how they could survive?

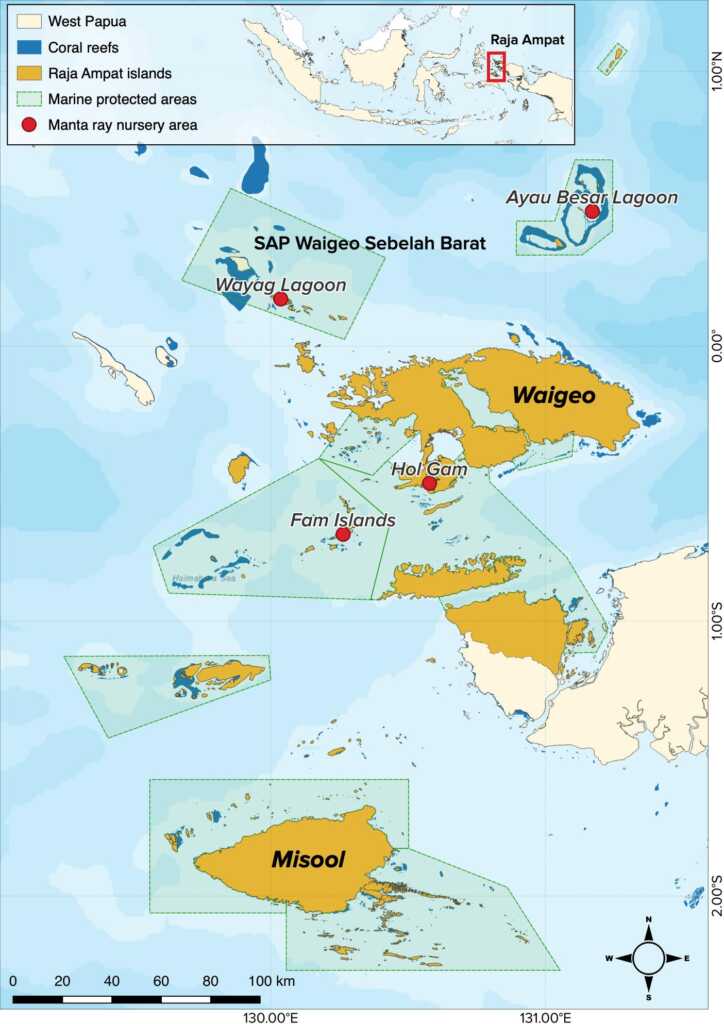

Until now, the early life stage of this giant fish is still a mystery. Most studies on manta rays have been focusing more on adult individuals than the youngsters. Well, the research undertaken since 2013 has successfully uncovered some of these mysteries. The study, published in Frontiers in Marine Science, provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date description of how newborn and juvenile manta rays use the Wayag Lagoon in the northwest of Raja Ampat waters as their habitat for flourishing. This study is the first research to confirm the existence of manta ray nursery area in the world.

Manta ray nursery habitat

So far, there are only a handful of places globally that have been proposed as potential nursery areas for manta rays. These include the Gulf of Mexico (Flower Garden Banks and the southern coast of Florida, United States), Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, Maldives, and Indonesia (Nusa Penida and Raja Ampat).

In Raja Ampat, we have identified four potential areas, namely the Fam Islands, Hol Gam, Ayau Besar Lagoon, and Wayag Lagoon.

For newborn and juvenile manta rays, living in a nursery area is critical to ensure their survival. This area tends to have calm water, making it suitable for the young rays to learn swimming. This area also provides shelter from large predators, such as sharks.

In addition to providing a source of food, the nursery is a place where they can interact and “share experiences” with conspecifics.

An area is defined as “manta ray nursery habitat” if it meets the following three criteria:

- Newborn and juvenile manta rays are more commonly encountered in this area than in other areas

- Newborn and juvenile manta rays have a tendency to stay and/or return to this area for extended period

- The nursery area is used repeatedly by newborn and juvenile manta rays across years.

It is not an easy and quick task to fulfil these criteria to prove that Wayag lagoon serves as manta ray nursery. It requires various different approaches to complete the puzzle and fulfill those criteria.

How to track the young manta rays?

To fulfill the criteria above, we conducted fieldwork every 3-6 months from 2013–2021 in Wayag Lagoon. We used multidisciplinary approaches, including photographic identification (photo-ID), drones, satellite tracking equipped with GPS, and passive acoustic tracking (a system that works much like a biometric attendance machine).

Based on photo-ID, we managed to record 34 juvenile reef manta rays from 47 encounters. Five of these 34 juveniles were sighted and photographed again in the Wayag Lagoon after 16 months, including 2 juveniles resighted after 21 months.

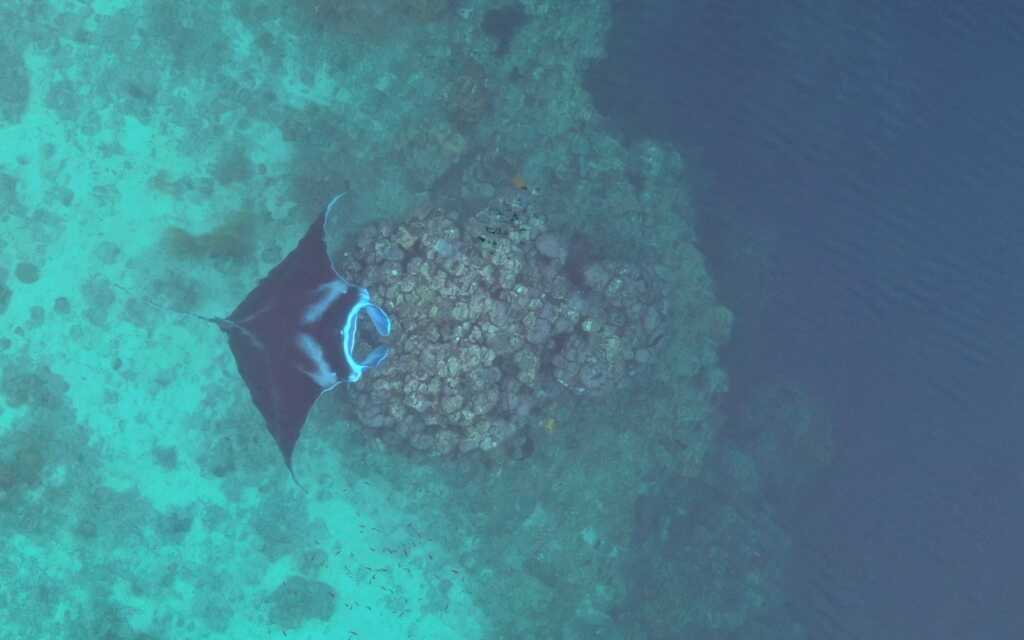

A juvenile reef manta ray is somersault feeding, showing a pattern of white spots on its underside (Photo by Edy Setyawan)

Each individual manta ray can be distinguished by unique spot patterns (just like our fingerprints) on the underside of their bodies. We can use this natural permanent marking to develop database of photo-identification. However, not all of the juveniles were able to be photographed properly in order to identify them. The waters inside the lagoon are typically murky, and often it is not easy to get close to the juveniles in the water.

In the lagoon, the juveniles are often seen somersault feeding on the sea surface or near surface. They also often seen cruising around the lagoon surrounded by towering karst islands. We also observed that young manta rays did not hang out with large adult manta rays.

Two juvenile reef manta rays feeding and cruising near a karst island in the Wayag Lagoon (Photo by Edy Setyawan)

In addition to photo-ID, we manage to estimate the disc width (DW) of the juveniles ranging from 150–240 cm with an average of 199 cm. Using a drone, we also measured two juveniles sized 218 cm wide and 219 cm in DW.

To determine the home range of the juveniles, we deployed GPS equipped satellite tags on 5 juveniles in the Wayag Lagoon in 2015 and 2017. After tracking for 12–69 days, we found these juveniles spent most of their time in the lagoon. They only occasionally ventured out of the lagoon for a few days to explore areas around Wayag before quickly returning to the lagoon.

A juvenile reef manta ray with an acoustic tag on the right side of its dorsum (Photo by Edy Setyawan)

Following satellite telemetry, we deployed acoustic transmitters in 9 juveniles and acoustic receivers in 5 sites inside the Wayag Lagoon to understand the residency pattern of the juveniles. Each transmitter has a unique code, so that any tagged juvenile detected in the vicinity of the acoustic receiver can be identified and its presence recorded.

Between May 2019 and September 2021, these acoustically tracked juveniles were detected nearly continuously for about 14.5 months in the Wayag Lagoon. The acoustic detections were recorded every single day for 4 months continuously. The juveniles were also detected “round the clock” in the lagoon.

A juvenile reef manta rays is visiting a cleaning station – a big bommie on coral reefs, home to cleaner fish serving manta rays as their clients (Photo by Edy Setyawan)

The Wayag lagoon also provides the juveniles with cleaning stations located on coral reefs. Like a “spa”, the juvenile manta rays visiting these stations enjoy the service from cleaner fish feeding on parasites on their bodies.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the juvenile manta rays are highly dependent on this nursery area for not only their health, but also survival.

What’s next?

The result of this study provides more robust and stronger evidence to findings published in the Journal of The Ocean Science Foundation two years ago. Both studies show that Raja Ampat in West Papua is important habitat for Indonesia’s largest populations of reef manta rays and oceanic manta rays (M. birostris).

However, there are still lots of unanswered questions. How long do juveniles stay in the nursery habitat until they leave this area? How do they interact with each other in the nursery? What factors influence their movements and spacial use within the relatively small area of Wayag Lagoon?

Finally, it is crucial to ensure that Wayag lagoon is well protected and properly managed to maintain its function as nursery for manta rays!

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the following institutions for their support of Wayag manta nursery conservation efforts: Masyarakat Adat Suku Kawe, The Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Balai Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional (BKKPN Kupang), The Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry, BLUD UPTD Pengelolaan KKP Kepulauan Raja Ampat, The West Papua Conservation Agency (BBKSDA Papua II), The Indonesian Manta Project, Manta Trust, Konservasi Indonesia, and Reef Check Indonesia.

Finally, we’d like to thank the following donors that supported research and conservation of the Wayag manta nursery: MAC3 Impact Philanthropies, Sunbridge Foundation, Wolcott Henry Foundation, Save the Blue Foundation, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, SEA Aquarium Singapore, Ray Dalio Foundation, Sea Sanctuaries Trust, Stellar Blue Fund, Seth Neiman, Katrine Bosley, Alex and Sybilla Balkanski, Marie-Elizabeth Mali, Daniel Roozen, Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF), Russell E. Train Education for Nature (EFN) Program, New Zealand ASEAN Scholarship

*Edy Setyawan is Bird’s Head Seascape’s manta ray researcher and doctoral candidate at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.