The Story of EPI and The Pursuit of Inclusive Shark Science by Made Abiyoga Udaya

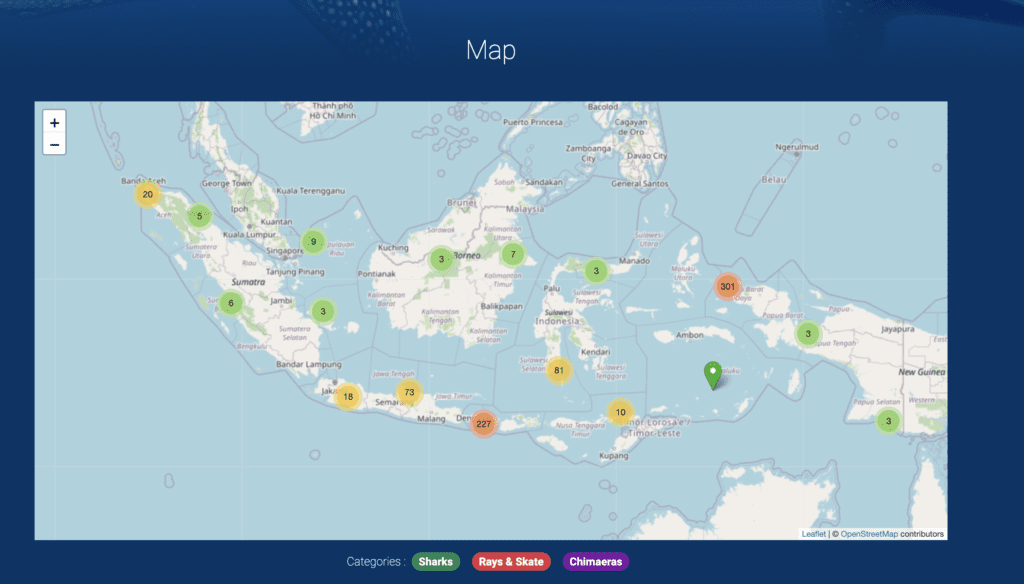

Among the myriad of marine species described globally are a group of cartilaginous fish, known as elasmobranchs. Ranging in size from mere centimeters to tens of meters, this extensive group inhabit all depths of the ocean. Indonesia, the largest archipelagic nation in the world, is home to over 200 elasmobranch species – almost a fifth of all the known species worldwide. Unfortunately, these high numbers have challenged scientists studying elasmobranchs, creating inequalities regarding what is known about various elasmobranch species.

While the charismatic nature of some species, whale sharks and manta rays, for example, has made them a high priority in research and conservation, others considered to be less charismatic are often overlooked. We can even agree that a third group of elasmobranchs (other than sharks and rays), known as chimaeras, remain unknown to most. Accessibility to species-specific data remain poor, and Indonesia’s vast area, complex market chains, and lack of adequate fisheries data in remote regions have all hindered the growth of elasmobranch science.

Such issues led two highly driven, young marine scientists to set out and turn the tide. In 2020, Elasmobranch Project Indonesia (EPI) was developed by Faqih Akbar Alghozali and Maula Nadia to fill knowledge gaps while simultaneously driving a nation-wide collaboration between elasmobranch scientists and the general public. The belief that everyone, regardless of background, can help expand scientific knowledge prompted the development of EPI’s “citizen science” approach. Citizen science is a collaborative practice where members of the general public can directly participate in science and research, and EPI provides a platform for the public to submit their elasmobranch encounters in Indonesia. During its 4 years of operation, EPI has collected over 800 reports of elasmobranch encounters comprising 104 species across 25 provinces.

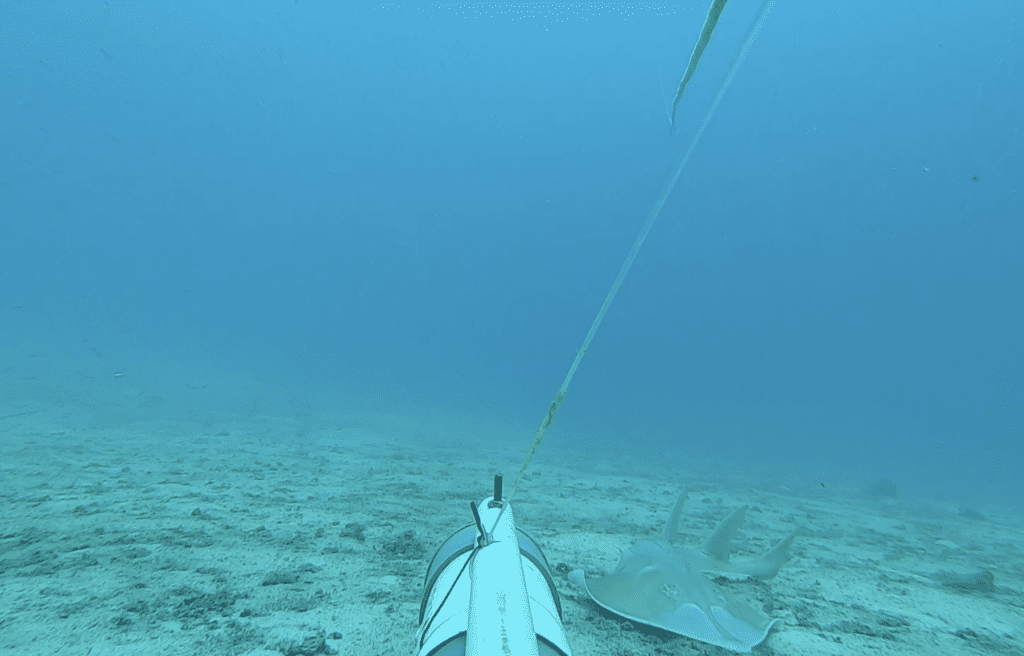

While the project was being developed, an accidental discovery led the EPI team to expand and conduct their first field-based research project at Karimunjawa National Park, off the north coast of central Java, as their initial study location. A trip to this site found Faqih on a fishing boat with an associate. As the fishermen hauled their nets, Faqih saw a species he did not expect- a giant guitarfish (Galucostegus typus). Conversations with the locals revealed that the guitarfish is a species often encountered and caught. This overlooked information pushed EPI to initiate their Rhinorays Project in 2022, using (BRUV) Baited Remote Underwater Video surveys to study the local population.

EPI’s main mission is to map the biodiversity and distribution of elasmobranchs in Indonesia. To accomplish this goal the project is designed to provide a space where anyone interested is given the direct opportunity to participate in elasmobranch science in Indonesia. The success of EPI’s citizen science approach reeled in numerous sighting reports throughout the nation. One that particularly stood out was that of a walking shark species, the Raja Ampat epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium freycineti) in Raja Ampat, West Papua. In science, more findings bring about more questions, and the walking sharks of Raja Ampat posed many questions worth answering.

Earlier this year, the Kalabia Project, named after the walking shark’s Papuan name was launched with the goal of better understanding the population abundance, distribution, and threats faced by this species. For the initial phase of this project, the waters surrounding Arborek and Yenbuba villages were selected as the two appropriate research sites. The field team uses a capture-mark-recapture method to collect data that will be used to develop a database of individual sharks. All sharks encountered are captured, measured, and sexed, as well as photographed for visual identification. The information obtained about each individual shark is then collated and recorded within EPI’s database. Within the past month, the team’s effort around Arborek alone have shown promising results that could take local walking shark population studies to the next level. EPI’s team has now moved to their second base, the village of Yenbuba, where they are eagerly anticipating identifying and recording walking sharks found on the western quadrant of Kri Island. Afterall, conducting science in some of the world’s richest marine habitats will be sure to keep you on your toes.

EPI’s efforts to develop an elasmobranch data base have yielded respectable results, and their data has been used by several research bodies and conservation NGOs. Bridging the gaps of current science is no easy feat, but a great effort that EPI has decided to pursue. Their database is only the foundation of the extensive work that they hope to achieve long term.

Keep checking the BHS site for exciting updates from EPI’s field team: their discoveries, challenges, and scientific contributions to our knowledge of Indonesia’s elasmobranch population.

To learn more about EPI’s work, visit their website, social media pages and submit your images:

www.elasmobranch.id

@elasmobranchid

Made Abiyoga Udaya is the Research and Conservation Officer for Thrive Conservation.