Indonesia Gives Mantas A New ‘Ray of Hope’

This post was originally published on Conservation International’s blog, Human Nature.

Mark Erdmann has been working closely with the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries on the development of Indonesia’s new regulation protecting its manta rays. Here he reflects upon the ministry’s enlightened approach to valuing its marine resources and some of the field work which Conservation International is now leading to further inform manta ray management in Indonesia.

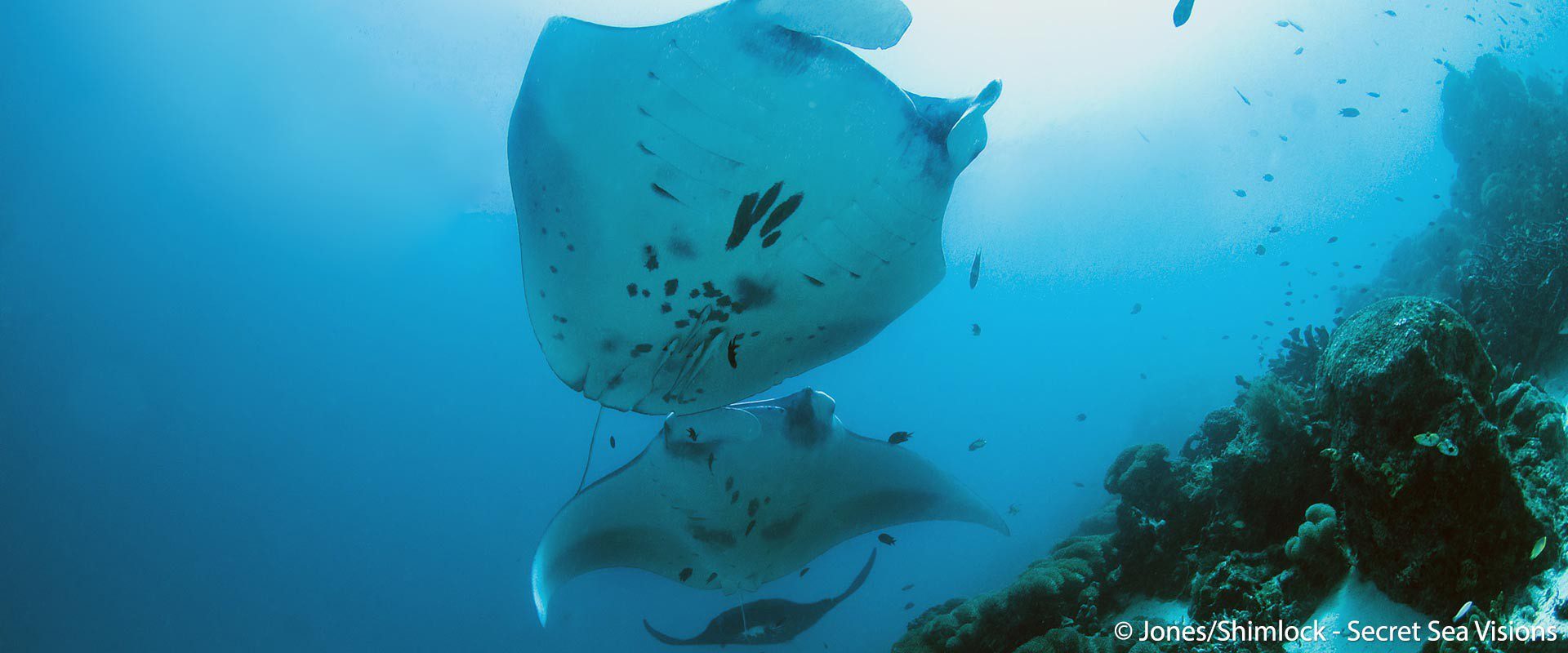

Things just keep looking brighter for Indonesia’s long-suffering elasmobranchs, a subclass that includes sharks and rays.

A year ago, CI and partners celebrated the bold move of the Raja Ampat government in passing tough new legislation to create the first shark and ray sanctuary in the Coral Triangle — a decision that was largely driven by the government’s realization that its sharks are not only important for sustaining healthy fish stocks for its people, but also that sharks and rays are an incredibly valuable asset to its burgeoning marine tourism industry.

Shortly thereafter, our partners at MantaWatch and Coral Reef Alliance worked with the local government and dive operators in Komodo National Park to set up Indonesia’s second shark and ray sanctuary in that marine tourism hotspot.

Around the same time, the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries hosted the first national symposium on shark and ray conservation, and the minister himself appointed a working group to consider options for potentially listing Indonesia’s most threatened elasmobranchs as protected species.

On February 20, 2014, the minister of fisheries proudly announced the first legal product to emerge from that working group’s recommendations — full protection for both species of manta ray — in a gala launching ceremony in Jakarta, complete with a 20-foot manta balloon brought to the party by our partner WildAid.

This new regulation makes Indonesia the world’s largest manta sanctuary, totaling nearly 6 million square kilometers (2.3 million square miles) in size!

A Lesson in “Mantanomics”

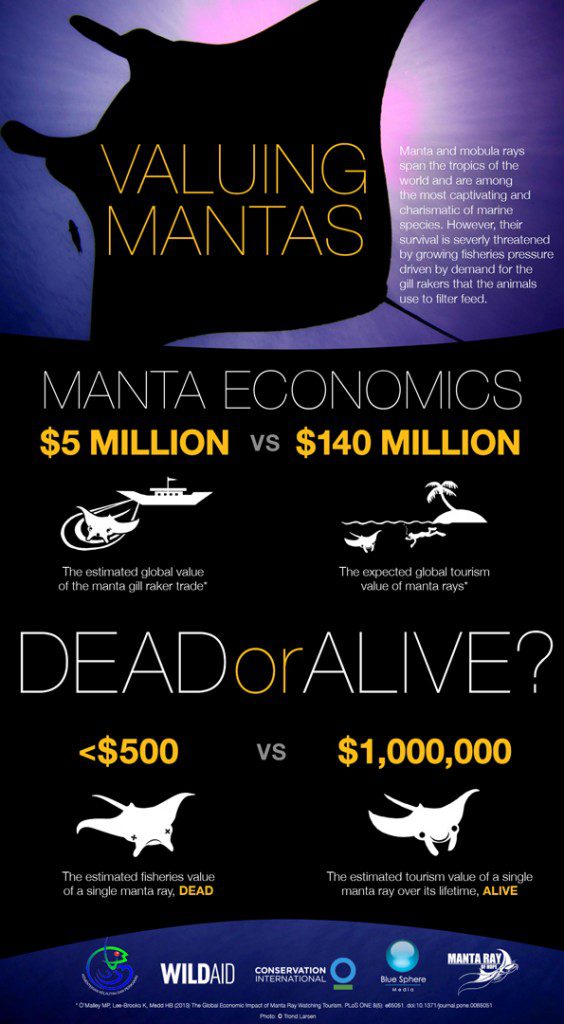

Importantly, the minister’s decision to protect Indonesia’s mantas was also largely an economic one. The working group’s recommendations focused on what I like to

call “mantanomics” — specifically, that aing manta ray is easily worth 2,000 times its value dead as a fisheries product for an obscure Chinese “medical product” that uses dried manta gills.

These gentle and majestic giants are a top draw for divers and snorkelers, and Indonesia already boasts the second-largest manta tourism industry in the world. Again and again, we are seeing that proper economic analyses that account for all the potential values of nature show conclusively that sustainable use of our natural capital — the benefits and services that nature provides to people — is the only prudent way forward.

Studying Mantas — and Sharing What We Know

Now that Indonesia’s mantas are legally protected, we of course face a new challenge to properly manage their threatened populations and assist the Indonesian government in broadly socializing the new regulation and enforcing it when needed.

To achieve this, CI has been working with a number of partners over the past six months. On the socialization side, perhaps our most effective partnership has been with Indonesian media celebrity and shark lover Riyanni Djangkaru. Riyanni is truly a master of social media, and her Save Sharks Indonesia campaign has had a dramatic role in increasing the awareness — particularly among Indonesia’s urban populations — that shark and ray fishing is unsustainable.

At the same time, we’ve been working with Manta Trust, Misool Baseftin and the Indonesia Manta Project to census Raja Ampat’s manta populations and to conduct satellite and acoustic tagging studies to determine their movements.

Understanding where mantas move within Indonesian waters is critical to managing their populations. Recent work by the Aquatic Alliance, MantaWatch and dive operators in Bali and Komodo has shown conclusively that reef mantas regularly move between Bali and Komodo — directly through known manta hunting grounds off South Lombok. This finding helps focus management efforts by the Indonesian government toward these hunting grounds in order to protect the highly valuable manta tourism industries in Komodo and Bali.

In Raja Ampat, we’re not sure yet how far these mantas might move, and if they are regularly crossing into dangerous waters. To address this, we’ve begun a large-scale tagging program, including testing some prototype new “towed” satellite tags, which trail slightly behind the tagged mantas and are able to quickly send a GPS position to orbiting satellites within seconds of the mantas coming to the surface to feed.

These new tags provide near real-time data on manta movements, which will be enormously valuable in managing Indonesia’s mantas. Our first two prototype tags have been transmitting high-resolution data over the past few months; we are now discussing a large-scale manta tagging program focused across Indonesia in collaboration with Singapore’s SEA Aquarium and the Indonesian Institute of Sciences.

There’s still lots to do to ensure effective implementation of the new regulation, but today we are taking a pause to celebrate this exciting “ray of hope” for Indonesia’s mantas!