Study: Mining could disrupt (Raja’s) Manta ‘Superhighway’ by Conservation International’s Mary Kate McCoy

Administrator’s Note: This blog post by Conservation International‘s Mary Kate Mc Coy was originally posted on May 30, 2024. It is shared with CI’s kind permission.

“If you’re a reef manta, there are few better places to be than northeastern Indonesia.

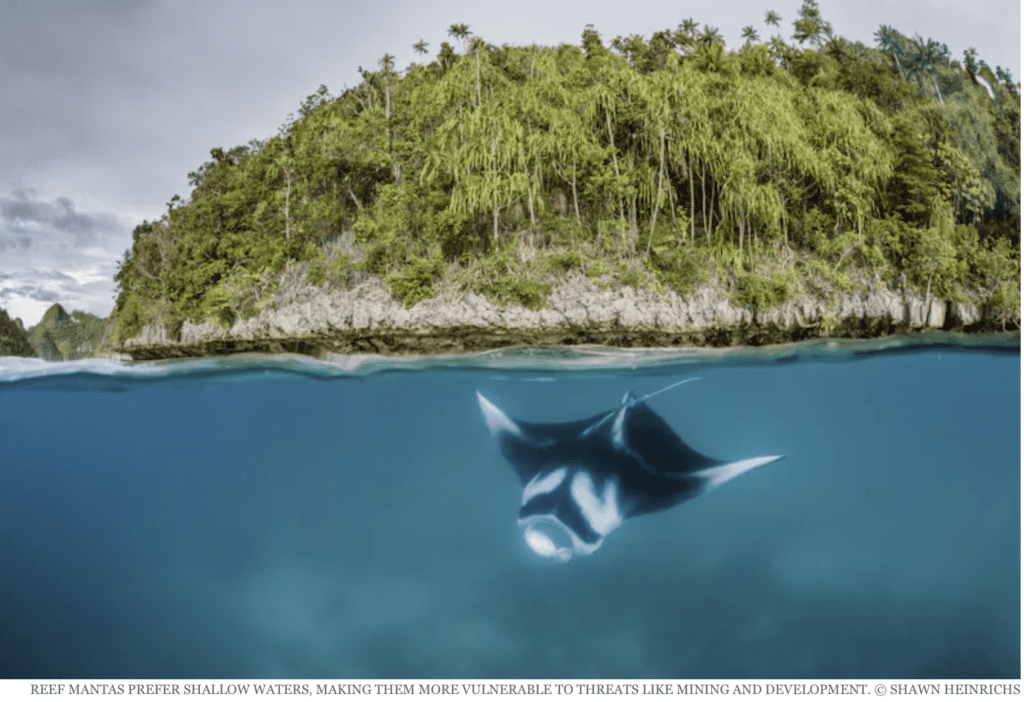

In the clear blue seas of the Raja Ampat archipelago, these marine giants — up to 4 meters, or 14 feet, in wingspan — are thriving. In fact, it’s the only place on Earth where their populations are growing, thanks to strong marine protections dating back more than a decade.

Now, research from Conservation International and its local partner, Konservasi Indonesia, is renewing concerns about a threat to these pristine waters: nickel mining.

Experts worry that rising prices for the precious metal, spurred by growing demand for electric vehicles, could imperil a critical habitat just outside of Raja Ampat’s vast marine protected areas, which span 6.7 million hectares (16.5 million acres) — an area twice the size of Taiwan.”

“Using data from more than 30 acoustic sensors, researchers tracked the movements of more than 70 adult manta rays and discovered that they spend much of their time in an area known as Eagle Rock, located outside Raja Ampat’s protections.

The mantas flock to Eagle Rock because it is an essential ‘cleaning station’, where fish like wrasse and scarlet cleaner shrimp remove parasites and dead tissue from the mantas.

Trouble is, Eagle Rock is situated near known deposits of nickel.

“We’ve long observed mantas feeding and cleaning at Eagle Rock, but we had no idea how important it was to them,” said Mark Erdmann, a Conservation International marine biologist and study co-author. “Eagle Rock is like a fueling station along a manta superhighway — they all stop there for cleaning, which is critical for their health, as well as to feed on abundant plankton during the falling tide.”

Erdmann said Eagle Rock was previously left out of protections because experts thought the surrounding protections were sufficient. But the new study shows otherwise.

By tracing the movement patterns of Raja Ampat’s manta rays, the researchers discovered that instead of one large population, they belong to three separate “sub-populations” that tend to stay close to home. While they can travel hundreds of kilometers, they rarely do, instead traveling between neighboring feeding sites and cleaning stations.

That means that protections need to align with the feeding sites and cleaning stations of each individual subpopulation — not one large population, Erdmann said. The researchers now know that the majority of the mantas from Raja Ampat’s largest subpopulation use Eagle Rock as a critical hub and stopover in their movements between feeding areas.

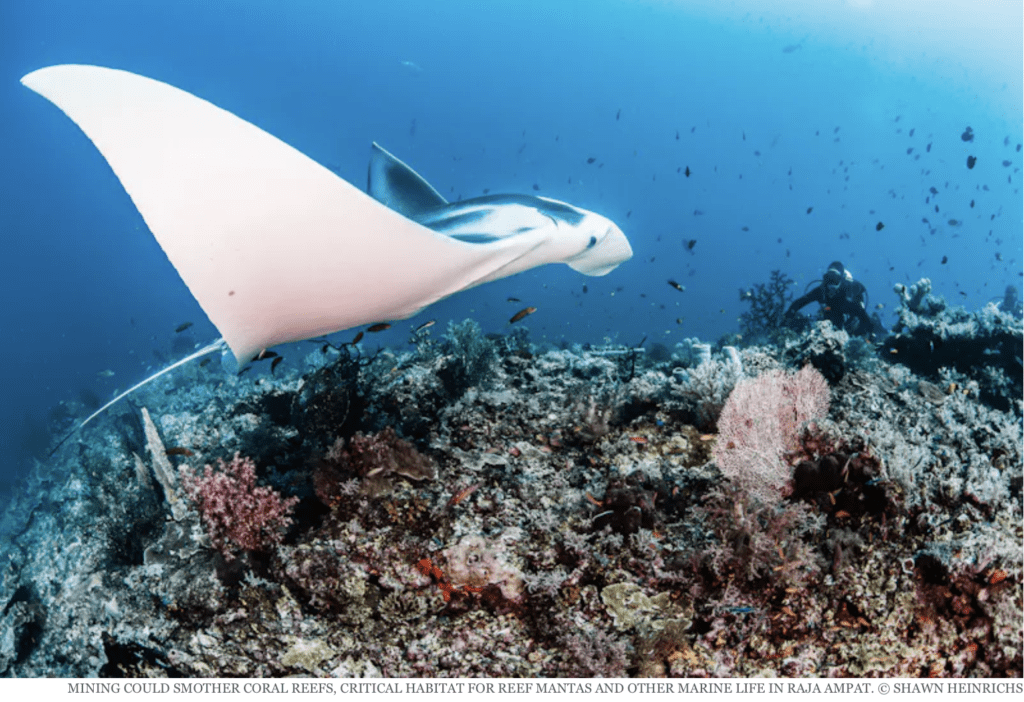

If mining were to be allowed on Kawe Island, near Eagle Rock, the results could be devastating for the manta rays.

“We’re very concerned about the potential for nickel mining near Eagle Rock for two main reasons,” Erdmann said. “Kawe is a mountainous island with steep terrain, and it rains a lot. If [mining companies] start open-pit mining on Kawe, every rain will produce muddy run-off that will flow straight into the ocean. And that will be disastrous for manta rays.”

For one, manta rays are filter feeders — if their feeding areas become clouded with muddy water, they’ll simply leave, Erdmann said. And second, sedimentation from an open mine will eventually smother the coral reefs, which are home to the fish that clean the mantas and feed nearby local communities.

“If Eagle Rock ceases to function as a primary spot for feeding and cleaning, it’s likely to dramatically alter manta movement patterns in northern Raja Ampat, which could lead to declines in the health of the manta population,” he explained.

And it isn’t just mantas that would be devasted by mining on Kawe Island, said Roberth Mandosir, Konservasi Indonesia’s lead in western Papua. The coral reefs that could be smothered by runoff are vital for countless other species, including endangered sharks and sea turtles.

The reefs are also an economic lifeline for local communities. Last year, they drew 25,500 tourists, more than twice the number that visited in 2022, according to the Raja Ampat Marine Protected Area’s Management Authority.

The researchers plan to use the study’s findings to rally support to prevent nickel mining in the area and to extend the marine protected areas to include Eagle Rock. Erdmann is optimistic they will be successful given that Raja Ampat is classified as an area of strategic national importance for marine biodiversity, and the growing concern within Indonesia for the negative impacts of mining in small island environments.

Ultimately, the new study reinforces that a deep understanding of how species exist in their habitats can improve conservation efforts, Erdmann said.

“What we’ve learned about manta ray movement patterns is likely true of other large marine life, such as dolphins or whale sharks,” he said. “Now, we must translate these insights into action.”

Mary Kate McCoy is a staff writer at Conservation International.