Cenderawasih Bay: Living Laboratory of Evolution, text and photographs by Dr. Gerald Allen

Cenderawasih Bay: Living Laboratory of Evolution

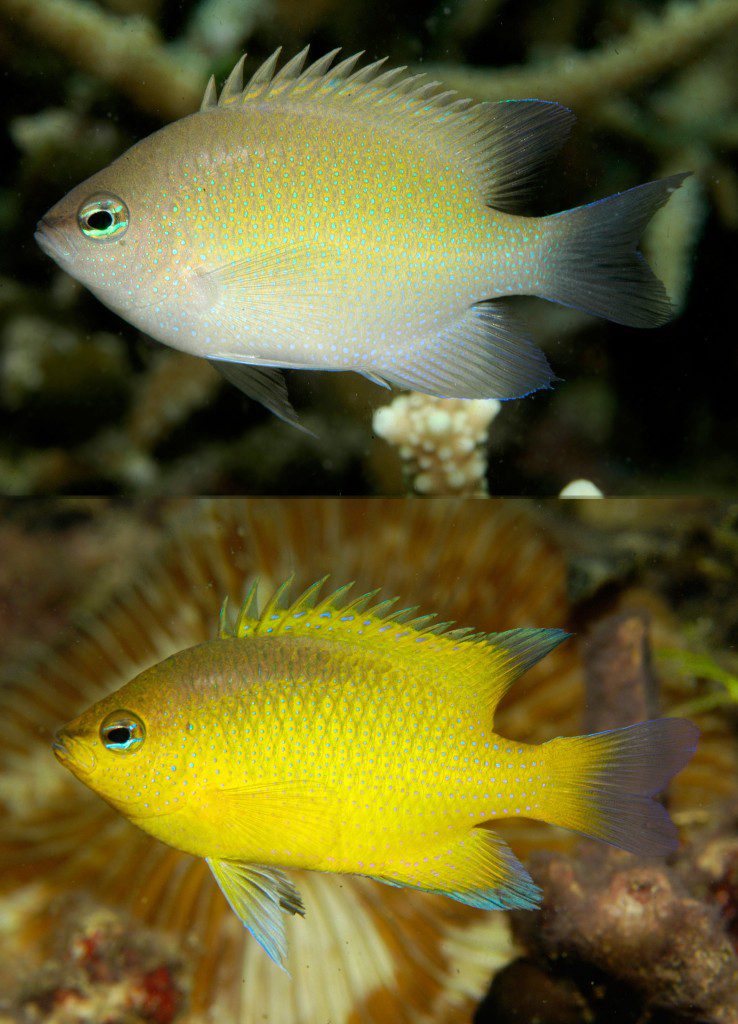

Several marine biological surveys by the authors and colleagues during 2006-2010 at Cenderawasih Bay, West Papua uncovered a wealth of new species, including at least 15 fish and 18 coral species that appear to be endemic to the inner portion of the bay. New discoveries of this magnitude are unparalleled in our experience for such a relatively confined area. At least five additional species, including Chrysiptera oxycephalus, Neoglyphidodon nigroris, and Pomacentrus albimaculus (Pomacentridae), Halichoeres rubricephalus (Labridae), and Meiacanthus grammistes (Blenniidae), exhibit unusual colour pattern variations that differ compared to conspecific populations from adjoining regions (Raja Ampat Islands and Papua New Guinea). These species are currently the subject of genetic studies that may provide additional evidence for the recognition of at least some of these as distinct species.

Cenderawasih Bay endemics (top to bottom): Pterocaesio monikae (Caesionidae); Paracheilinus walton (Labridae); Chrysiptera pricei (Pomacentridae); Cirrhilabrus cenderawasih (Labridae) © G. Allen

The Cenderawasih Bay fish community is further characterized by the unusually shallow occurrence (4-8 m) of a number of species (Cephalopholis spiloparea, Chaetodon burgessi, Centropyge multifasciatus, Chromis alpha, Pomacentrus nigromarginata, Halichoeres melasmapomus, Acanthurus nubilus, and Xanthichthys auromarginatus) that are generally confined to depths below about 20-30 m at most locations in the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, the angelfish Genicanthus bellus was regularly observed in 20-30 m compared to its usual depth range below 45-50 m. Finally, genetic studies of connectivity patterns among marine organisms by Paul Barber and his students (e.g., Barber et al, 2006; Crandall et al, 2008; DeBoer et al, 2008) have noted the presence of distinctive clades in Cenderawasih Bay for several molluscs and crustaceans. Based on the biological evidence summarised above, we hypothesize that the inner portion of the bay was essentially isolated for a substantial period over the past five million years.

Color variation in Chrysiptera oxycephala: Raja Ampat (upper) and Cenderawasih Bay (lower) © G. Allen

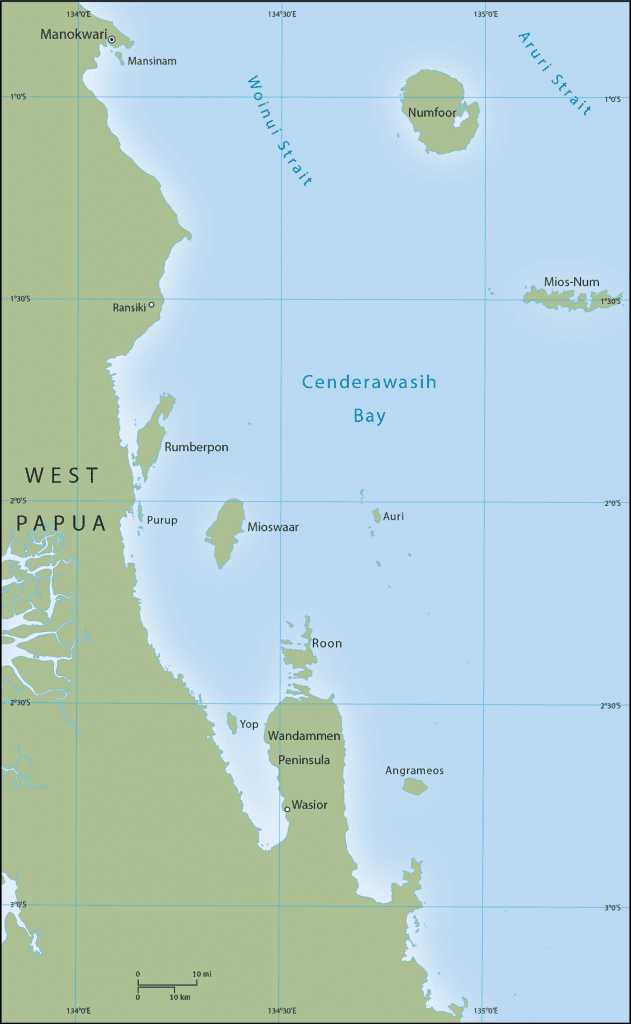

The paleoreconstruction of the south-western Pacific region by Hill and Hall (2003) incorporates a wealth of new data to provide a better understanding of the tectonic processes that have shaped the region’s geology over the past 50 million years. According to their model a series of island arc terranes arose along the edge of the Caroline Plate, eventually collided with the Australian Plate, and then slid parallel to the northern coast of New Guinea before eventually accreting to form the northern ranges. The latter event occurred relatively recently, probably over the past million years. The accretions were emplaced in a west to east series, with the oldest blocks being sutured in the far west. One of these arc terranes, known as the Tosem Block (Hill and Hall, 2003) slid across the entrance of Cenderawasih Bay between about 2-5 million years ago (Fig. 3) (see reconstruction above) before finally docking along the northern edge of the Bird’s Head Peninsula. We believe this process effectively isolated the bay, thus setting the stage for the evolution of its amazing suite of endemic species.

Fluctuating sea levels is another factor that surely played an isolating role. The Bay is remarkably deep (in excess of 1600 m in several places), but Yapen Island and a shallow (mainly less than 100 m) sill form a barrier of sorts between the outer and inner bays. Isolation was greatly amplified by fluctuating sea levels working in tandem with the shifting arc terranes. Over the past 150,000 years alone there have been two major lowerings of up to 130 m and numerous smaller fluctuations. Sea level changes are most likely responsible for the depth range anomalies. The Bay is steep-sided with very limited shallow reef-flat habitat, which would have been virtually eliminated during even moderate sea-level drops. The absence of shallow water competitors allowed the deep reef species – especially those living on steep slopes – to invade shallow water. As sea levels rose again, some of the shallow species re-colonized, but limited oceanographic circulation prevented large-scale repopulation by shallow fishes and apparently at least some of the deep species have been able to maintain their dominance in shallow water. Even today, recruitment into the Bay may be less than ideal due to the deflection of seasonal ocean currents by the islands at the mouth of the Bay and large land masses on either side.

Reconstruction of Cenderawasih Bay approximately 2.5-3.0 MYA showing the migrating Tosem Block, forming a barrier across the entrance. This arc terrane eventually docked with the northern Bird’s Head Peninsula immediately to the west.

Allen, Gerald R. from Allen, G.R. & Erdmann, M. V. 2012. Reef Fishes of the East Indies. Volumes I-III. Tropical Research, Perth, Australia, Vol. I pp. 28-29 (Reef Fishes of the East Indies)

Dr. Allen is the “world’s leading tropical marine fish expert”.